LCA is a methodology for assessing environmental impacts associated with all the stages of the life-cycle of products, processes, or services. It can be used to create benchmarks in order to set targets for impact reduction or as a tool for comparative decision making. However, the method is increasingly coming under fire as the purveyor of less than sound or counterintuitive conclusions that might favour continued industrialization rather than a move towards a more harmonious relationship with the planet.

The reasons for this and ideas for how LCAs can be rectified are discussed in our new report for Break Free From Plastic (BFFP). The following is a summary of key findings:

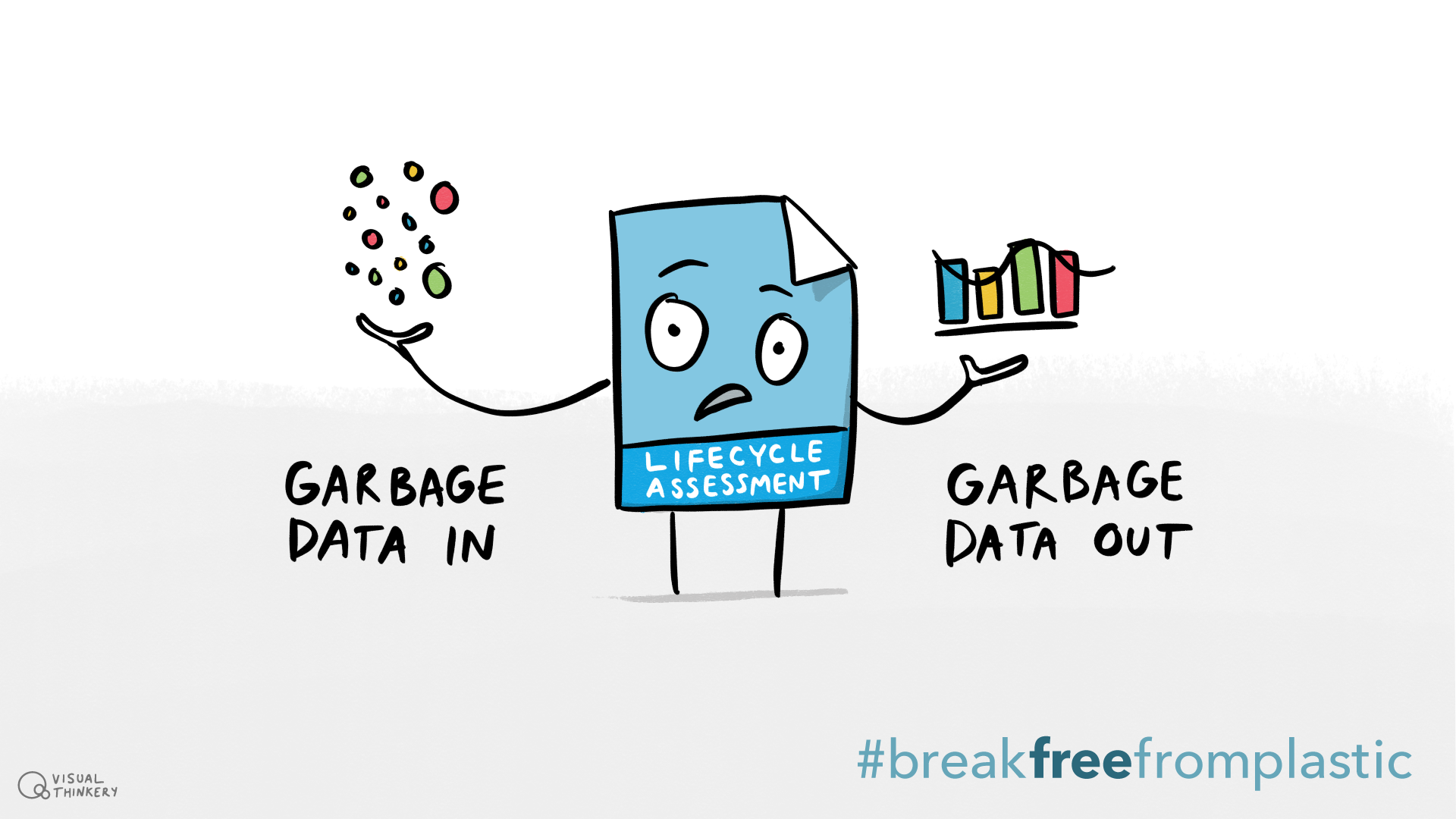

◾ Firstly, it’s important to recognise that LCA is merely a tool, and like many tools can be wielded inefficiently or incorrectly. It is used to answer a question and therefore the context and nature of the question will determine the answer. Whenever anyone asks me, “what is better, X or Y?” the answer is always “it depends”. It depends upon a whole series of assumptions as we attempt to create a simplified model of reality that can be used to answer that question, but is it also important to determine whether the question itself is the ‘right’ one in the first place. Why do we want a comparison between X and Y? what about Z? What if we changed the whole system so that X, Y and Z did not need to exist? What if the question were not which material is ‘better’ or is single-use better than reusable, but how can we design reusable systems that have the least environmental impact? A key aspect of this is design i.e. not looking at static systems, but understanding the design parameters we can change to optimise the environmental performance of the product or system.

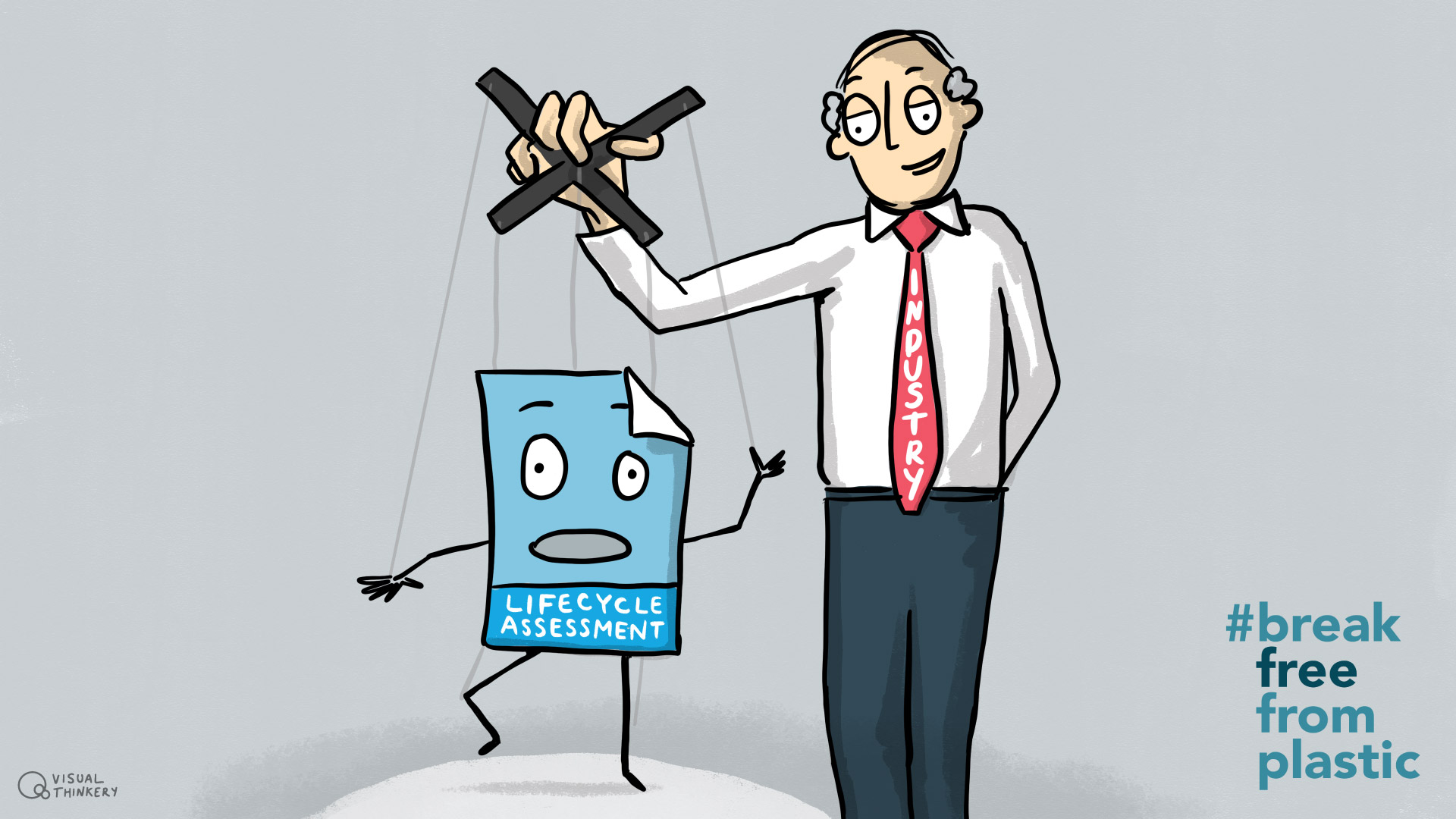

◾ Businesses will almost always look to answer the narrower and more limiting questions and therefore receive answers in that similar vein—these answers can also be used to promote their products and the system they have created as the only ‘truth’. Making bigger decisions at a national or supranational level requires a broader perspective that can often be lacking. It is only by going back and questioning our fundamental assumptions that we can get to an objective truth.

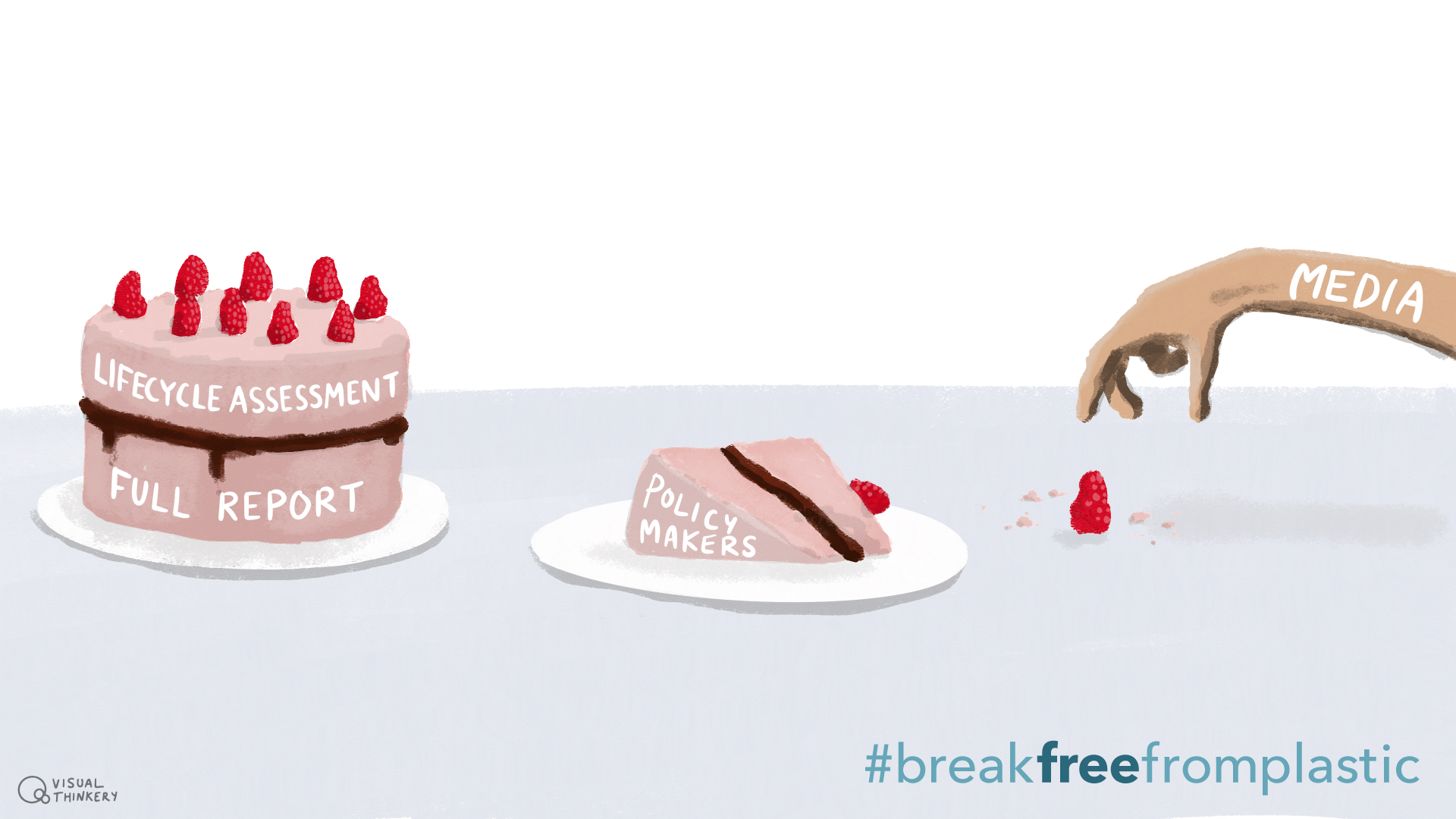

◾ There is also the problem of communication when the results of an LCA study find their way into news headlines. This is similar to how we might often read about the results of a scientific study that has just been published in a journal. Often the studies are aimed at specialist audiences and therefore can often be misinterpreted by non-specialists. They are also not viewed in the context of the body of work that already exists; just like we don’t usually assume one scientific paper will change our world view of science on its own, so the findings of one LCA study should not override all existing work in order to grab headlines. Having a good understanding of the context in which the study sits and the importance of any accompanying assumptions is critical to interpreting it. And just like studies that might appear that say eating certain foods might increase health risks there are also ones that say the opposite and this can be true with LCA. These studies are generally not meant for public consumption or to influence individual behaviours (should I stop drinking coffee or should I buy that reusable bag or not?), but to aid in the wider discussion.

These issues are nothing new to LCA practitioners, but they are not insurmountable. For example, practitioners themselves can be more cautious around only presenting their strongest and defensible results. They can attempt to understand the policy context in which their study sits and advise their clients accordingly. For the study commissioners themselves, it is important to aim to be as open and transparent as possible and be mindful of making claims beyond that which the study is valid for.

Finally, for those reading these studies, recognising that the results are only as good as the question is a good start; questioning the very premise of the study can provide a new perspective. Realising that there are no absolute answers is also helpful, and just like any scientific paper, if we are to take the results seriously, looking for an independent peer review can give some security that an expert has already undertaken at least some due diligence on your behalf.

Read “Plastics: Can Life Cycle Assessment Rise to the Challenge? (How to critically assess LCA for policy making)” here:

About the Author:

Simon Hann specialises in applying Life Cycle Thinking wherever a full understanding of how a product or process affects its environment may be needed, and is a Principal Consultant and LCA Specialist for Eunomia Research & Consulting, Ltd. His work looks into how diverse activities can contribute to our evolution into a society that embraces a Circular Economy. Much of Simon’s work is linked to how we can make this transition by keeping materials and resources within our technosphere.