In the state of Gujarat, #breakfreefromplastic member Paryavaran Mitra, an environmental organization that aims to increase public participation in government decision-making, is appealing to authorities to acknowledge the essential role waste pickers have in keeping the environment clean and safe, especially as COVID-19 continues to spread. The group is demanding that the government provide waste pickers livelihood and policies that will help protect them.

Unregulated rates and inadequate policy

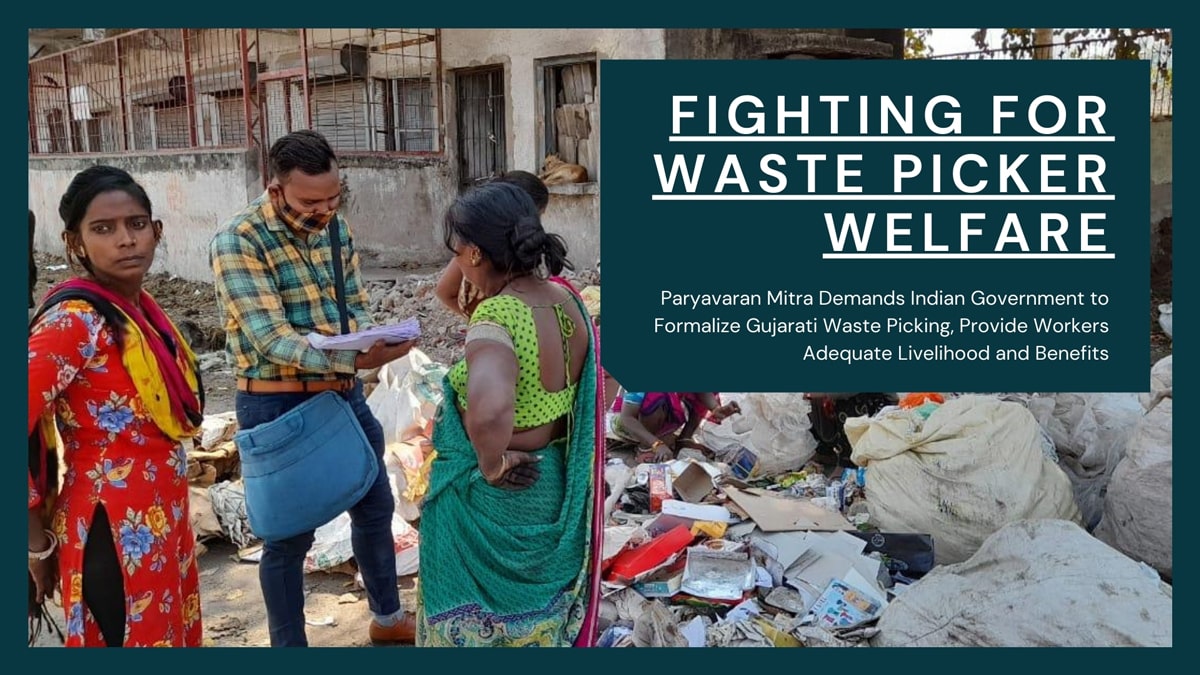

In a conversation with environmental and human rights activist Mahesh Pandya, director of Paryavaran Mitra, shared that informal waste pickers in Gujarat are in dire need of assistance. He points out that many of them come from outlying areas going into cities looking for jobs, and would end up collecting discards to sell. “They do not have a residence to stay, and so they stay on the roadside or in open land, no roof above them. They are collecting plastic waste from the city without any hygienic instruments, haphazardly going without gloves as they collect waste. It is a very risky job that without a mask or without gloves [they get exposed] not only to the coronavirus but other bacterial diseases that are there.”

Photo caption: Paryavaran Mitra’s Falguni Joshi (left) and Mahesh Pandya (right)

Paryavaran Mitra’s Falguni Joshi adds, “The living conditions are very bad. They don’t have proper housing facilities and sanitation facilities. And because they don’t have any recognition from the government, they are not entitled to get any social sector help.”

Pandya says that many of these workers would end up involving their entire families in collecting waste, and would only receive about fifty to a hundred INR (around 00.69 to 1.39 USD) in total for an entire day’s work. In India, the minimum wage per individual is around 268-293 INR for unskilled/semi-skilled/skilled workers (roughly 3-4 USD). He says that this is largely due to the informal nature of the trade. Informal waste pickers aren’t able to sell to recycling centers directly and so would sell to those willing to buy at unregulated prices.

“They are collecting the plastic waste, they are helping my state, my country, and the whole world. And they are doing this kind of humble work. The government should come forward and give designated minimum salary, minimum wages, and minimum livelihood facility to them,” says Pandya.

Then there is also the issue of the insurmountable trash in Gujarat. “There is no systematic mechanism to reduce the waste. We are working a little bit but not up to the mark, and particularly plastic we are not able to have a plastic waste collection center. There is no plastic separation waste system and all,” he adds.

Pirana Landfill in the city of Ahmedabad

Pirana Landfill as seen from afar

The waste has accumulated in dumpsites like those in the Pirana Landfill found in the city of Ahmedabad, which has been gaining infamy due to the many dangers that threaten the safety not just of informal pickers within but also the surrounding areas. People living inside the city have gotten used to the sight of the massive mounds of trash that even children now assume it’s a normal mountain found within. Joshi recalls an incident in the past where two children, unfortunately, got buried when a mound of waste collapsed.

Formalizing Recognition and Going Zero Waste

Paryavaran Mitra has been sending recommendations to the chief minister of the Gujarat state and the prime minister of India to address these issues. Part of their appeal is to provide waste pickers facilities to bathe and wash up to keep themselves clean and safe from diseases. They also hope the government can provide them some shelter and food. Ultimately, they are fighting to formalize the occupation.

One suggestion that was raised is for the government to cover waste picking under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. The act, passed in 2005, secures livelihood for individuals in rural areas, guaranteeing them the “right to work”. The law mandates that adult members of a household will be provided at least a hundred days of wage employment if they volunteer for unskilled manual work, which Pandya believes can easily include waste picking.

They also suggest that if the government can’t provide these, then they can look to corporations within Gujarat for funding.

“We also stated a number of examples to the government that you can collect money from the industries under corporate social responsibility (CSR) or under the extended responsibility of industries who are generating the plastic. Collect the sales from them, and with this, you can use it for the plastic waste pickers. That is our simple demand.”

Part of formalizing this is also to create a proper structure for waste collection within Gujarat, which means investing in infrastructure and manpower. However, Paryavaran Mitra recognizes that even with the proper collection, much of the waste cannot be resold or recycled. So their longer-term goal is to help cities in the state become zero waste -- a goal that the city of Ahmedabad has already promised to achieve by 2031.

The zero waste pledge by the city was made in 2013, but Joshi notes that they have yet to see concrete action from the government. Paryavaran Mitra believes there need to be opportunities for stakeholders to express their concerns on the matter, and so their group has been hard at work to pull in representatives from the sectors involved -- waste pickers included.

“Our focus is on increasing the public participation in the decision-making process. So when we found out that there was a recent document for becoming a zero-waste city [from the government], we were surprised because we were never consulted as civil society members. So we are thinking that if possible they can consult the waste pickers,” says Joshi.

Paryavaran Mitra training photo taken January 2020

Paryavaran Mitra Youth Mega Event taken July 2018

About Paryavaran Mitra

Paryavaran Mitra is a Gujarat-based organization that fights for social justice, focusing on environmental issues. The organization also has a publication meant to educate the academe, the legislative and judiciary arms of the government, and the general public. Their work began when their team noticed harmful fluorochemical contaminations in their water sources, traced back to the factories of corporations within the state. They are a volunteer-based, non-profit NGO.

This article was written by Julian Carlos Cirineo based on an interview with Mahesh Pandya and Falguni Joshi of Paryavaran Mitra. You may reach Julian at julian@breakfreefromplastic.org. To get in touch with Paryavaran Mitra directly, you can email them at paryavaranmitra502@gmail.com.