Von Hernandez, Global Coordinator of #BreakFreeFromPlastic

Estelle Eonnet : Have you already taken a toxic tour in real life?

Von Hernandez : I actually did a real-life toxic tour across South Asia in the late 1990’s, when we were investigating and documenting the toxic legacies left behind by DDT manufacturing operations and the stockpiling of obsolete pesticides. We traveled around India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Nepal, linking with local activists and following the trail of these persistent poisons, which in earlier times were considered to be miracle chemicals.

I remember really getting sick after that trip. I was hospitalized, my immune system crashed and I suffered from near heart failure. And we were just walking into these hot spots to document and investigate. Can you imagine the toll it takes on your physical well-being when you actually live near or around these toxic sites?

In the Philippines, I also worked closely with a community living beside a lead smelter that was being run by a company illegally importing scrap lead batteries from abroad. There was a recurring pattern in the stories shared by the old folk and the farmers living around this factory. Strange smells at specific times of the day, fishermen experiencing a decline in their river catch, local folks suffering from respiratory ailments — — these stories were then validated with scientific evidence, which proved that the river and farm land around the vicinity of the smelter had serious lead contamination. Community residents and workers from the plant were also found to have very high levels of lead in their blood.

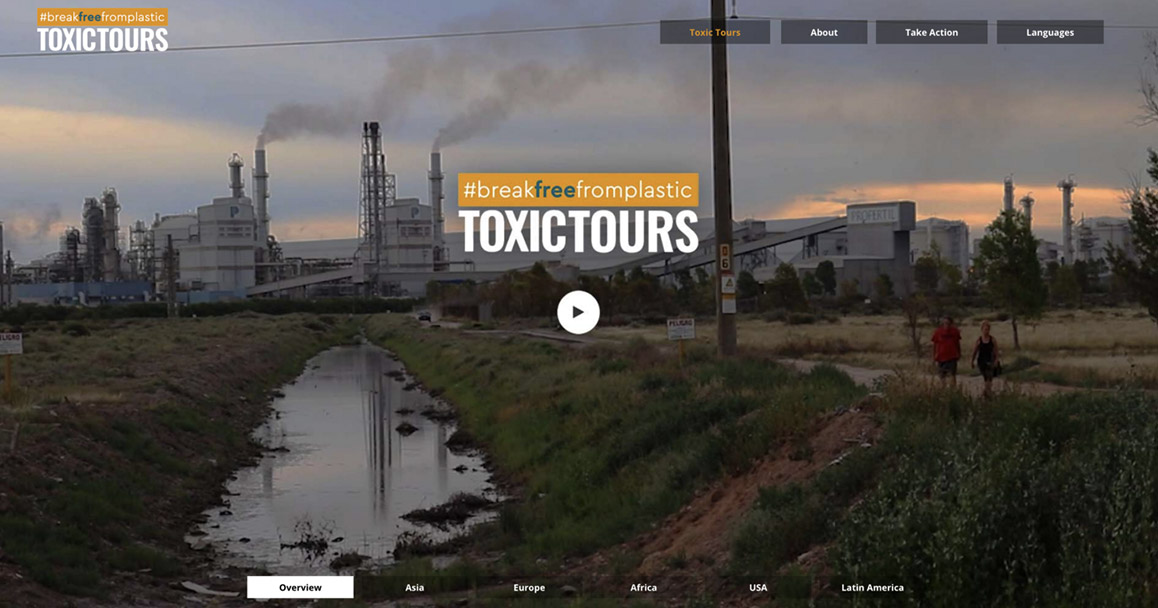

Manali, India.

Why build a platform that amplifies the stories of frontline communities living near plastic production sites?

It is very powerful to hear the impacts from those who are living under the shadow of a polluting factory. Global plastic production is projected to double in the next 15 years, becoming the oil and petrochemical industry’s Plan B as the world decarbonizes and moves away from fossil fuels. These multinational corporations view plastic as the economic lifeline that can keep their shareholders happy, albeit at the expense of people and planet.

On many levels, the Toxic Tours shows that this industry strategy is a global issue. Communities are victimized and sacrificed in pursuit of plastic production around the world. We need to make sure all site fights are being heard. Giving communities that are directly affected by plastic production a platform to tell their stories is empowering. By confronting the threats at their doorsteps and sharing their struggles, communities begin to take control of their destinies.

The platform also shows that there is deep and widespread solidarity on this issue. And for us, it’s about connecting the dots and allowing the movement to amplify the stories of toxic trespass and human rights violations associated with the whole plastics lifecycle.

How do the Toxic Tours impact the people’s understanding of single-use plastic?

The Toxic Tours allow us to reframe the narrative around plastics and blow the lid off of many of the myths that have been promoted and reinforced by industry, either to downplay the issue by saying that recycling is the solution, or evade its responsibility for the crisis by pinning the blame on individuals or local governments through their clean-up and various PR campaigns. The platform also establishes clear links between fossil fuels and plastics — and therefore the inescapable connections between climate change and plastic pollution — that both are in fact spawned by our societies’ continued dependence on fossil fuels.

For the general public, the Toxic Tours will be an eye opener, allowing individuals to see how systemic reliance on single-use plastic is creating an ecological nightmare for many communities in many places around the world.

The locations show site fights at very different moments in their development — in Kenya, in Taiwan. What are the similarities between the Toxic Tour stories?

One common thread with these dirty projects is that the host communities are always the first to be affected, but often the last to know. A polluting factory gets erected in their vicinity, but the communities soon discover that they have been left out of the decision making process. Even the economic or other direct benefits that are supposed to accrue to them as host communities are not felt. Yet they are first to suffer the immediate consequences of pollution.

Communities in the front lines also find that their fates are often in the hands of government regulators, who rely on “arbitrary pollution standards” that are not even consistently enforced.

The burden of proving harm often falls on communities. To outsmart this unfair system, many communities and local groups have taken to organizing themselves as “bucket brigades” or citizen scientists to monitor and uncover evidence of the pollution they experience.

Antwerp, Belgium

What role do you see the Toxic Tours playing in advancing advocacy? We had a huge win at UNEA with the adoption of a landmark mandate calling for the development of a global treaty on plastics. What are the next steps?

The Toxic Tours are significant in the wake of the UNEA decision. The recognition that plastics is not just a marine pollution issue, and that we need to be looking at its full life cycle is already a milestone in itself. In this context, showcasing the story of plastic upstream, where the problem starts, becomes even more important.

In the process of negotiating this global treaty on plastics, we want to highlight the rights of frontline communities, and the role of key stakeholders in the plastics value chain, like the waste pickers and informal sector. This is also an opportunity for governments to seriously consider upscaling and mainstreaming real solutions to the crisis, specifically reuse and refill systems — and not be mesmerized by the false solutions and techno-fixes being pushed by an industry desperate to maintain the status quo.

In this anticipated battle of narratives, the Toxic Tours becomes a crucial tool not only for truth telling but also for highlighting how the issue of plastic pollution intersects with other critical issues, including human rights, environmental justice and climate change.

The Toxic Tours local stories were produce by environmental justice and frontline groups from impacted communities, and the platform was produced by the #breakfreefromplastic movement with the financial support of the Plastic Solutions Fund. The Center for International Environmental Law also generously funded the Toxic Tours in Texas.

To take the Toxic Tours visit toxictours.org

Share about your experience using #ToxicTours and #breakfreefromplastic

For inquiries about the project, email us at toxictours@breakfreefromplastic.org

#breakfreefromplastic (BFFP) is a global movement envisioning a future free from plastic pollution. Since its launch in 2016, more than 2,000 organizations and 11,000 individual supporters from across the world have joined the movement to demand massive reductions in single-use plastics and push for lasting solutions to the plastic pollution crisis. BFFP member organizations and individuals share the shared values of environmental protection and social justice and work together through a holistic approach to bring about systemic change. This means tackling plastic pollution across the whole plastics value chain — from extraction to disposal — focusing on prevention rather than cure and providing effective solutions.