Silliman’s campus grounds provide a respite for students shuttling between classes

Built to last forever but made to be thrown away, single-use plastics are threatening the planet’s health. People are waking up to the devastating effects the persistent material has on the natural environment. One university in the Philippines is taking the lead in addressing the problem of plastic pollution and other solid waste on campus in the country.

Located in Dumaguete City in Negros Oriental, Philippines, Silliman University is a picturesque 117-year-old campus home to over 300 towering acacia trees, overlooking the sea. It is a university that considers environmental stewardship as one of its key responsibilities.

In 2018, the university welcomed a new President, Dr. Betty Cernol-McCann, whose leadership ushered in significant changes in the university’s efforts to improve solid waste management on campus. “We will intensify our drive against one-use plastics and prohibit bringing to campus containers and wraps that contribute heavily to waste pollution,” said Dr. McCann.

Recognizing that effecting change entailed getting a critical mass of people, Dr. McCann and visiting scientist and adjunct professor Dr. Jorge Emmanuel formed a Waste Management Committee at the beginning of the school year. They invited stakeholders from all across the university, from Academic Affairs to the Student Council. According to Dr. Jorge, “[They] wanted to make sure there were representatives from the faculty, staff, and students.”

One of the first things the committee worked on was the policy framework. The document presents five policies for all members of the university to follow. These are the: (1) General Policies on Waste Prevention and Waste Management, (2) Green Procurement Policies, (3) Policies Related to Food and Food Waste, (4) Waste Policies Related to Events and Festivals, and (5) Policies Related to Greening of the Campus. Silliman’s goal is 90% diversion from landfill.

Among their top priorities is the proper labeling of all the 800 bins on campus, after a recent waste audit found that majority of the bins contained mixed waste. To ensure that the instructions would be easy to follow, the committee came up with color-coded pictographs with words in both English and the local language, Bisaya, to serve as labels.

The committee will then organize a massive information and education campaign that will include the creation of posters, flyers, and videos. However, members of the committee are convinced that these measures will only be effective if people take the time to talk to their peers about the issues one-on-one. To do this, each department and unit is to nominate two environmental champions who will assist in awareness-raising campaigns and monitoring.

“A major aspect of our work is what we do with food waste,” said Dr. Emmanuel. Food Services at Silliman University is a centralized unit with 8 outlets and 90 employees throughout the campus. They serve the 1,000 people who enter their doors every day as well as the eight dormitories inside the campus.

They have taken significant steps to eliminate single-use plastics such as ceasing the sale of bottled water, juices, and fruit teas; they make their own healthy fruit juices instead. They have also stopped buying baked goods—which usually came in single-use plastics—and have been baking their own cookies. They serve brewed coffee instead of instant 3-in-1 coffee that comes in sachets. The department is adamant that they reach their zero waste goal “even if it means decreasing our revenue,” said Food Services Head Anna Vee Riconalla.

The Food Services Department (headed by Ms. Anna Vee Riconalla) has taken significant steps towards eliminating single-use plastics like opting to bake their own cookies and make their own healthy juices

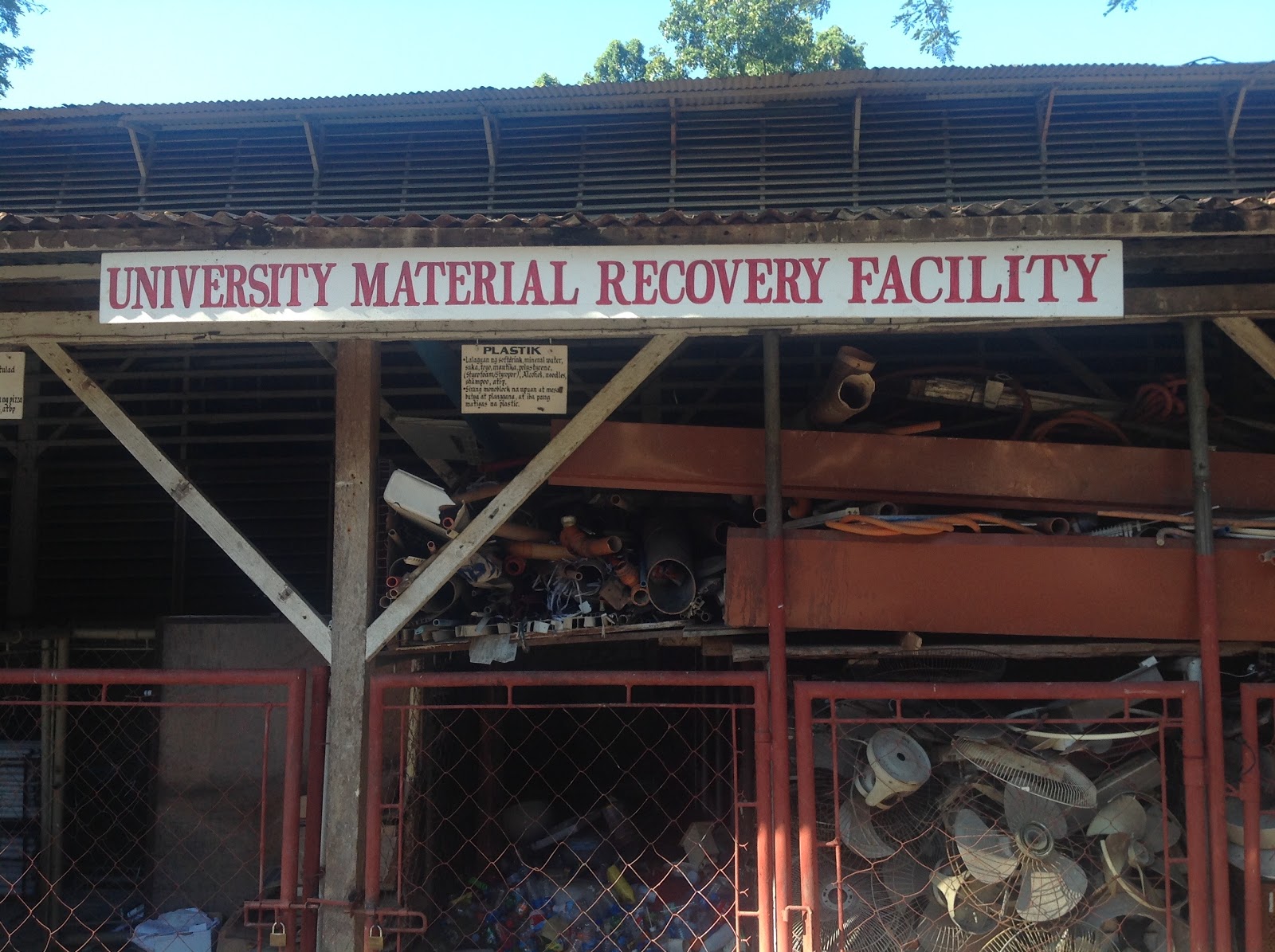

Another crucial element in solid waste management is Silliman University’s very own Materials Recovery Facility (MRF). The facility recovers materials such as plastics, oil, metals, batteries, and medical waste. Silliman sells their recyclables such as paper, plastic bottles, and metal to local junk shops.

The university’s MRF is home to a wide range of recovered materials such as old vehicles and used cooking oil to medical waste such as vials and syringes.

For example, for two years now, they have been using a nifty system in janitorial services to avoid mismanaged waste. Before any member of the janitorial staff can withdraw supplies from the storeroom, they have to return empty bottles of cleaning solutions, soap, disinfectants, as well as broomsticks, broken garbage cans, and faucets.

About a kilometer from campus, the university has a piece of property where they take their food and gardening waste for natural decomposition. They use the compost for landscaping around the campus.

One of the major problems they encountered was the huge number of glass bottles that accumulated on Silliman beach. They found mountains of glass bottles on the beach so they had the bottles loaded onto a cement mixer for crushing, together with some metal rods and huge rocks. They now mix in the crushed glass in their foundation.

The Waste Management committee believes that more than improving solid waste management efforts, the focus should really be on minimizing the use of plastics. But the problem, according to Engr. Ygnalaga, Head of the Buildings and Grounds Unit, is “Everything now is plastic. And when you buy something it then becomes your responsibility, not the manufacturers. They should include in their research how to bring it back again to the start…and for me, I will not be voting for incinerators.”

For him, the government should put more pressure on the manufacturers to take back their waste and redesign their products. “That’s the second part,” said Engr. Ygnalaga. “When you have these materials after you’ve bought them, it will be you who will spend money to bring it back to them [the manufacturers]. Why is it that way?”

Meanwhile, for Dr. Emmanuel, it’s not just about minimizing plastic use and waste on campus; it’s also about educating students to be responsible citizens. According to him, “One of our principles is that we want every student that graduates from the university to leave Silliman with a stronger sense of environmental protection and the competence on how to do it. We have to make sure, at the very least, that they know how to segregate at source so they can do it at home as required by law or when they travel abroad and they go to countries that already do very good segregation, that they don’t screw up another country’s segregation because they don’t know what they’re doing…so they can actually become good global citizens.”